So far in this short series on the basics of Integral thought, we’ve looked at quadrants — the belief that we need to look at things from as many perspectives as possible — and lines of development — the belief that human growth and maturity involve the whole person. Together, these two aspects give Integral Christianity a holistic orientation. Nothing is outside its scope of interest; its goal is for us to grow into fullness in every area of life. Today’s post explores the value and nature of growth itself.

As I’ve written previously, growth is a major metaphor in the our Scriptures for understanding the transformation the life of faith brings. Psalm 1, for example, frames a good life in terms of a flourishing and fruitful tree, as opposed to withered grasses. Similarly, in one of my favorite passages, Paul urges the Christians in Ephesus to “no longer be children” but “to come … to maturity, to the full stature of Christ” and to “grow up in every way” (Eph. 4.11-16; cf. Hebrew 5, where the writer complains his congregation still needs milk when they should be eating solid food by now).

This orientation towards growth is found in Integral theory in what is called stages of consciousness, or development. This idea claims that growth occurs in distinct and recognizable stages, and, like the lines of development, is borrowed from developmental psychology. When we look at the growth of children, we understand that there are different stages of growth, which are each marked by specific and predictable ways of thinking and acting. So, we think nothing of it when we see babies exploring their environment by putting things in their mouths, but if we were to see a ten-year-old do this, we would start asking questions. Similarly, we fully expect that in and around puberty adolescents will start to look to their peer groups for acceptance, beliefs and values, instead of their families. Such changes are expected, predictable, and, more or less, universal. Stages like these have been demonstrated on many developmental lines, such as cognition (in the work of Piaget and others), spirituality (Fowler), and socialization (Gilligan). While we think of development primarily in terms of growing from childhood into adulthood, psychologists have also found that we can continue to develop throughout adulthood as well. Some examples of this include the processes known as self-actualization or individuation on the cognitive line, and the “reflective,” “conjunctive,” and “universal” stages on the spiritual line. It is this continued growth through adulthood that really captures the interest of Integral thinkers.

Integral thought has expanded on the basic insight that growth occurs in distinct stages in three interesting ways:

First, it has attempted to generalize the patterns of development seen across all of the lines. This is to say that it has tried to find a common theme for what growth looks like in different areas of life. What it has come up with is that each stage of development is able to manage more data than the stage that came before it. So for example, with Gilligan’s stages of social development, we grow from caring only about ourselves, through caring for those closest to us, to caring for all others. Similarly, Fowler’s stages of faith demonstrate an increasing capacity to allow for complexity of the world, from a magical belief that we are at the centre of the world, through fixed mythological beliefs that shape community identity, to a more flexible faith system that accepts the world in all of its complexities. Critically, Integral theory understands that growth is not necessarily a good in and of itself; it can be healthy or unhealthy. Healthy growth, according to this model, transcends a previous stage while including its wisdom; unhealthy growth transcends the previous stage but rejects everything about it — as though one were to forget how to walk upon learning how to ride a bike.

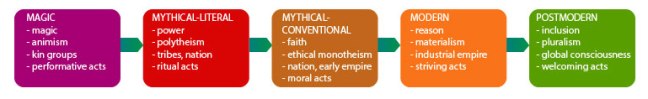

Second, Integral thought has created language to discuss the similar stages on each of the lines of development. The most common approach gives each stage a name describing its common features and a colour as a shorthand:

- Magic (Magenta)

- Mythical-Literal (Red)

- Mythical-Conventional (Amber)

- Modern (Orange)

- Postmodern (Green)

- Integral (Teal)

This predicts that a certain stage of development on the cognitive line will share certain characteristics with specific stages on the other lines. Perhaps the clearest example of this is the modern, or ‘orange’ stage, which applies the same logical approach to all of the lines, with reason dominating the cognitive and spiritual lines, and rationally-based, ‘universal’ human rights emerging on the moral line.

Third, and most controversially, Integral theory applies these stages of development to groups, societies and cultures as well as to individuals. The idea is that, since a culture is made up of the people within it, it will take on the aggregate characteristics of those people. One way to think about this is to imagine us all as drops of dye going into a tub of water: If most of us are ‘orange’, then the water is going to be largely orange as well. Conversely, the culture also shapes the people within it: if you are raised in orange-dyed water, you are more than likely going to end up orange.

While descriptively useful, this component of Integral thought has proven controversial since it would seem, however unintentionally, to lay the groundwork for a justification of the ‘superiority’ of some cultures and groups to others. This is a very serious concern — and one that is very close to my heart — and which deserves a fuller exploration than I can provide in this post. Right now, I’ll simply provide the following bullet points suggesting why I don’t think these legitimate concerns are cause to reject the developmental model itself:

- The primary usefulness of the stages is for individuals, and only by extension, and as an aggregate, and in general, descriptive terms, applied to groups

- When Integral thinkers talk about development, they are talking in terms of cognitive structures — the conceptual elements that govern how we engage with the world — and not about material culture

- This aspect of Integral thought, like all others, is guided by the “All Quadrants, All Lines” principle, so we have to be careful not to make blanket assumptions about groups. For example, it’s tempting to think of contemporary conservative evangelical Christianity as an ‘amber’ group based on its ‘mythical-conventional’ religious commitments; however, the evangelical approach to reading the Bible is very rationalist (‘orange’), and we’re seeing a strengthening authoritarian (‘red’) impulse in its politics.

- Any hierarchy this model implies is developmental and descriptive, and not a hierarchy of power or domination

- The model defines its terms clearly and therefore any claims it makes are constrained and specific

- Other aspects of the model insist that every human person and civilization has the right to be exactly who and where they are. The human genius has been and is expressed at every stage in cultures around the world

- Growth is understood as a natural unfolding from within; just an acorn would only grow into an oak, so too would any person or culture develop into each stage in its own unique way. From this perspective, the Western attempt to refashion the world in its own image is rightly understood as deeply pathological

- Healthy growth is understood as including the wisdom of previous stages, not rejecting it. On this criterion, the West’s emergence into the orange Modern meme — which is really at the heart of the critique against this framework — was about as unhealthy as it could be.

With all this in mind, it might be fair to wonder what the ‘descriptive usefulness’ actually is, and how it relates to Christian faith. For me, the idea of developmental stages is very useful, in a number of ways.

First, it helps us to understand ourselves and others. For the most part, North American cultures are a mishmash of people operating on various lines at premodern, Modern, and postmodern stages. What the Integral model reminds us is that this has huge consequences for people’s values, beliefs, and thought processes. If we want to make any progress in healing our social and political divides, we need to learn how to talk to those who disagree with us on terms that make sense to them. A great example of this has been the recent movement of banks and investors — paragons of Modernity if there ever were! — away from extraction industries; this didn’t start because they had a great postmodern love for the environment, but because continued investment in these sectors no longer makes sense in terms of the very Modern priorities of dollars and cents and return on investment. In a similar way, progressives would do well to harness the power of story, myth, and existing community values in order to speak better to people coming from religiously conservative backgrounds. While there is a long way to go on a broader and institutional level, I have heard many positive stories of LGBTQ+ Mormons and their partners/spouses being accepted by their families, not through a Modernist claim to universal rights or a postmodern questioning of gender norms, but by framing their inclusion as a natural extension of the existing strong Mormon value of family. This doesn’t mean conversations across worldviews will be easy, but it at least provides a shared place where those conversations can take place.

Second, the stages of consciousness can help us to understand the Scriptures and the people who wrote them. I’ve written about this more fully in the Integral Hermeneutics series, but to summarize: To say that the Bible was written by traditional, premodern people hides the diversity we see within the text itself. The Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, shows the progression from a persona, kin-oriented ‘magenta’ religion (e.g., the promise made to Abraham and his children, and the altars set up by the Patriarchs at sites of personal religious importance), through the development of a ‘red’ cultic religion of a nation (e.g., the Law and the formalization of ritual based on the agricultural calendar and the nation’s history), to the ‘amber’ ethical monotheism represented by the Prophets (e.g., their promotion of justice over ritual practices as the true marker of faithfulness). Understanding this progression of thought within the Scriptures can help us better contextualize and interpret them — especially the passages that trouble us.

According to Integral theory, this movement in the Scriptures is not accidental, but is actually one of religion’s primary goals. Thus the third way developmental stages are helpful is what Ken Wilber has referred to as the ‘great conveyor belt’ of faith: Religious traditions, rituals, and experiences provide individuals with culturally-sanctioned guidance in moving from one developmental stage to the next. Since our Scriptures were codified at the ‘amber’ stage, they stop there, but they should guide us at the very least to ‘amber’ values of community and ethical monotheism. If they don’t do this, then we might have cause to worry that something is wrong with our religious systems. (See, for example, the previously mentioned ‘red’ authoritarian trend in the conservative American Christian landscape.) The conveyor belt idea also provides us with a further mission of exploring what ‘faithfulness’ might look like within our religious tradition at healthy expressions of the more recent stages. Certainly there were many different Christian responses to Modernism, ranging from fundamentalism to rationalist deism, but since the West’s move to Modernism was so unhealthy, it remains to be seen what a ‘healthy’ Modern Christianity might look like. We might similarly ask how healthy postmodern or Integral manifestations of Christianity might be faithfully expressed. (And indeed the latter of these is precisely the exercise of this series!)

This post has been rather technical, but to summarize: Integral theory understands that not only do humans grow in distinct stages, but that these stages can continue throughout adulthood in every area of life. Understanding these stages can help us to better understand ourselves and others and provide us with a roadmap for what might come next for us, our communities, and the world.

This series will continue with a look at the role of states of consciousness in Integral thought and our Christian tradition.

Please see the Annotated Bibliography on Integral Thought for sources, works cited, and further reading.

7 thoughts on “Integral Basics, Part 4: Stages of Development”