A few years ago, in my series on tradition, I wrote about how tradition always involves not just passive reception of the past, but active and intentional changes: “Tradition is an active process: we receive from the past but inevitably apply it to the needs of the present for the sake of our desired future.” Much the same can be said about our sacred, historical, or extreme places. Legacy is always being interpreted and reinterpreted. I hinted at this in my post the other day about different ways communities choose to preserve their ancient sites, but it really came to the fore for me during the last day-and-a-half of my recent trip, in Manchester.

While it’s a city with Roman foundations and a history of occupation throughout medieval and early modern times, Manchester didn’t come into its own until the Industrial Revolution. But where in most cities this would lead to there being a visible ‘old city’ with a new city built up around it, in Manchester development seems to have been steady all over, so that buildings from the sixteenth century are next to high Victorian buildings are next to structures from the 1970s, which are in turn next to contemporary steel and glass construction. It gives the city a very authentic and lived in feeling. (I acknowledge that some of this was not by choice; the architectural patchwork I so admire was in part due to the patchy impacts of the blitz during the Second World War.) Even something controversial, like the dismantling of a sixteenth-century pub and reassembling it piece by piece 300m down the street in the 1990s to accommodate new development at least shows an intentional grappling with the past done for the sake of the future. I think all this is wise; too often historical places can feel like Disneyfied tourist traps, completely separate from the surrounding neighbourhoods. I didn’t feel that at all in Manchester. It’s the mark, I think, of lasting vitality.

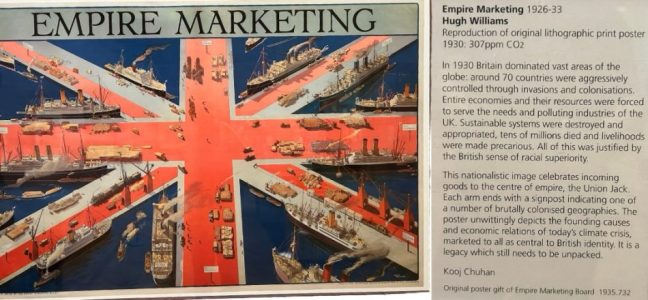

This intentional reckoning with the past, which I was already thinking about in terms of the architecture I was seeing around me, was revealed more explicitly in the city’s art gallery. There, instead of the standard tags simply stating a piece’s name, creator, and provenance, they printed full curatorial conversations about the piece, its meaning, and what it said about Manchester when it was created and what it says about the city today. It was completely fascinating. One of my favourites was a fantastic futurist/cubist painting by C.R.W. Nevinson of men playing football with a factory spewing smoke in the background. The panel next to it had one curator questioning whether it wasn’t just an English cliche, while another staff member defended its lasting relevance. But many of the displays also told and interrogated the city’s role as a centre of British Imperialism. Another piece (shown below), interpreted the lines on the union flag as streams from which the goods of the world could stream into England. Shown as a positive thing in the poster, through twenty-first century eyes it looks more like the imperial centre vacuuming up the wealth of conquered lands — a legacy openly discussed in the curatorial discussion.

While I have no doubt this curation is controversial — there are always a lot of people who want our stories told only with the most positive and heroic spins — I think it’s beautiful and necessary. Again, it’s part of what living in a tradition — and a society is a tradition — is about: active receipt and engagement with and interpretation of the past in the present for the sake of the future. It’s not easy, but it’s honest and necessary work.

It felt like a perfect note on which to end this trip, full as it was of ancient and sacred and beautiful places. When I ended my series on sacred practices many years ago now, I essentially concluded that anything can be a sacred practice and a place of encounter with God if we approach it as such and with intention. Very little in our experience of the world is about the facts of it, but is rather wholly dependent on the stories we tell about it. My delayed and more-involved-than-expected arrival in York could have just been a frustrating travel day. It’s possible to think of Durham as nothing other than a sleepy college town, or Lindisfarne as just one tidal island among dozens. We can look a Hadrian’s wall as a lasting memorial of one of history’s great Empires, or as simply a handy source of stones for fencing; and the hills of Northumberland and Cumbria as places of incredible beauty or as untapped potential for extraction industries. When so much depends on the stories we tell, we would do well to think long and hard about those stories and be intentional about telling the ones that connect us most to goodness, truth, and beauty.