As you’ve probably guessed by now, part of what made my recent travels feel like a pilgrimage — even those parts that didn’t hold religious significance — is the way the feeling of the transcendent followed me around, in all its many guises. We’ve already looked at the transcendence of numinous or holy places, of places of great historical significance, and of places on the edge of things. Today I’d like to focus on the transcendence of old, and especially ruined things.

The common core of transcendence is awe and humility: we encounter something that makes real for us just how small and insignificant we, our problems and concerns, are in the universe. Sacred places do this by connecting us with the ‘wholly otherness’ of the holy. Borderlands and other places at the extremes do this by connecting us to the possibilities and dangers of ‘what lies beyond’. Old and ruined things do this by reminding us of just how short our lives are in comparison to the long reach of history.

I say old and ruined because for me at least, both intact ancient structures and ruined ones give me this sense, albeit in different ways. In walking through an ancient building that’s still intact, like Durham Cathedral or Bamburgh Castle, or even one of the many medieval pubs we stumbled upon, it’s impossible not to think of all the people who have walked on those steps before us. (I remember very vividly my last trip to the UK in 2018 how surprisingly meaningful it was to receive communion at Canterbury Cathedral for this reason.) They, like us, in any century, would have had their worries and concerns, some trivial, some legitimately important. But those people are long gone, even as the buildings still stand. This was powerfully driven home tome on a trip to Rome a couple years ago; I was there during one of those moments when there was a real possibility that we could fall into a world war at any moment, and yet walking through a gateway that had seen the rise and fall of Empires, violent attacks, plagues and pandemics, times of political openness and repression, and wars upon wars, I couldn’t help but remember that like all of those times, ‘this too shall pass’.

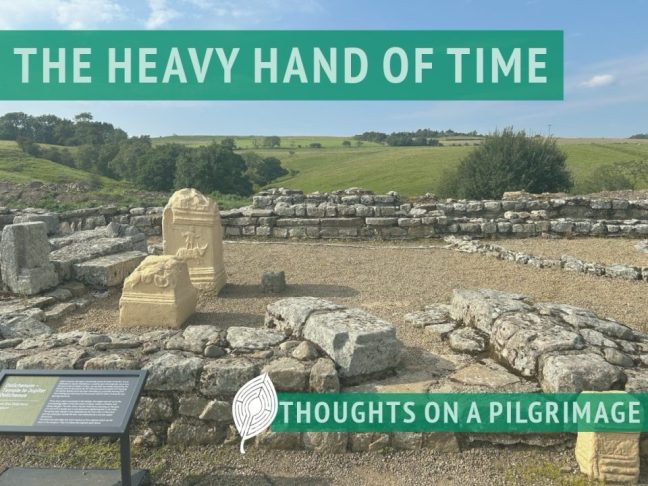

On the flip side, ruins confront us with the ravages of time, how even the most impressive human achievements inevitably crumble into dust. This was especially driven home to me on this trip when we visited the ruins of a temple to Mithras along Hadrian’s Wall and found sheep grazing inside it! The hand of time is very heavy and it comes for us all.

The miraculous thing about the transcendent though is that these feelings of humility and insignificance don’t render our lives meaningless, but rather make them all the more meaningful. Our time is limited and therefore our most valuable resource. Our shared human vocation is to make that time count, to leave a positive legacy and mark on the world. And yes, that legacy too will eventually pass away, but we trust that someone will take up the torch and carry on.