I’m a huge ancient history nerd. (I may not quite fit the ‘think about the Roman Empire every day’ meme from a couple years ago, but if you add in Persia, Egypt, Assyria, or Greece, I’m absolutely guilty as charged!) For this reason, I can never get enough of ruins, and Roman ruins are absolutely among my favourites. I once even took a course about Roman city planning, architecture, and building techniques. All this means that otherwise boring plots of stone ruins come alive for me as bathhouses and barracks. For this reason, visiting the remains of Hadrian’s Wall and walking through the ruins of Coria (Corbridge) and the forts of Vindolanda, Vercovicum (Househeads), and Magna (Carvoran) was a huge highlight of my trip. I wasn’t surprised by how much I enjoyed and appreciated these sites, but I was surprised by how incredibly Roman they were, even though they were literally at the very edge of the Empire, and by feeling of the transcendent I experienced walking through them. These were military or otherwise secular sites through and through. So why might I have had this reaction?

While it’s not often discussed, I’m convinced that extremity is actually a fairly common trait of the transcendent. This is the feeling we get standing at water’s edge on North America’s West Coast and realizing that the closest land beyond the horizon is in another continent, and that the whole mass of the entire continent is at our backs. It’s an incredible and humbling experience. This is the transcendence we experience at the edge of things. This was a feeling I encountered a lot in my recent travels: on the tidal island of Lindisfarne surrounded by the North Sea; at Lindisfarne and Bamburgh Castles, which had been defensive outposts along the English border with Scotland; and yes, especially along Hadrian’s Wall, which was for much of its active life the northern border of the Roman Empire.

The essential Romanness of these sites only exacerbated the feeling; as I looked north of the Wall and thought about how where I was was so common and ordinary in the Roman world, from there through to the Saharan and Arabian deserts, and yet nothing like it existed north of it.

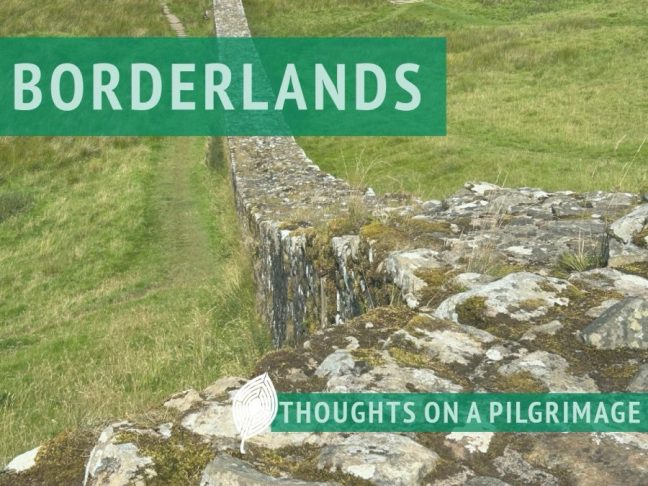

It was also fascinating to see how the wall itself was built to accentuate the rugged landscape; it was less a barrier in the places I visited than a reinforcement of existing natural barriers. The landscape to the north was so wild and rugged that I couldn’t help but keenly feel the sense of otherness and foreignness of what lay on the other side.

It was also fascinating to see how the wall itself was built to accentuate the rugged landscape; it was less a barrier in the places I visited than a reinforcement of existing natural barriers. The landscape to the north was so wild and rugged that I couldn’t help but keenly feel the sense of otherness and foreignness of what lay on the other side.

And yet no barrier or border is impermeable. There are gatehouses along the way and we know that over the centuries not only soldiers (friendly or enemy) but also villagers and traders would come through them. (For twenty years there was even another wall about 160 km to the north!) Likewise, Lindisfarne priory for all its isolation was visited by pilgrims — to say nothing of Vikings — and Bamburgh Castle did not exactly have a stellar record in battle. This is to say that borderlands are a kind of liminal space, portals between two worlds, between the familiar and the unknown, and the unknown itself is filled with both opportunities and risks. And maybe that’s what helps to give them their transcendent quality.

When we’re standing at the edge of something, somehow anything feels possible.

2 thoughts on “Borderlands”