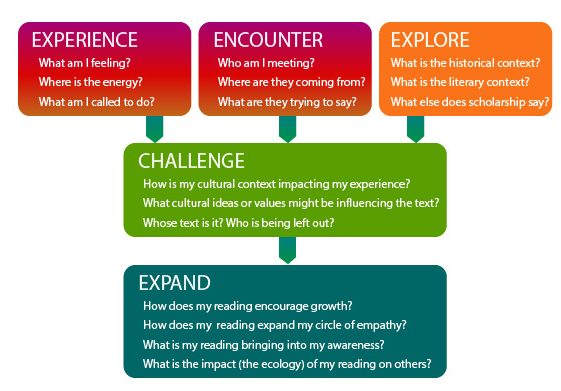

“In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth…” (Genesis 1.1). There are few more evocative words in all of the Jewish or Christian Scriptures than these, their very first. They begin, of course, the first of two creation stories recorded in Genesis. The passage as a whole stretches thirty-four verses, from Genesis 1.1 through 2.3 (as a shorthand I’ll just refer to it as the Genesis 1 story), and while there’s too much to say about it for just one post, there is also a lot that needs to be said about it as a whole, to set the stage for the details. So today I’ll be looking at the story in broad strokes before getting down to the details in the next few posts. As a reminder, these studies will be guided by my Integral Hermeneutic Method, with its five steps of Experience, Encounter, Explore, Challenge, and Expand:

Normally, I’d start by providing the text here, but because it’s so familiar and so long, and since we’ll be looking at it in greater detail over the coming days, I’ll simply link to it for today’s purposes: Genesis 1.1-2.3.

Experience

For some reason as I read this passage this morning what came to mind was the old definition of golf as “a good walk spoiled.” My first instincts whenever I read Genesis 1 are to praise God and exult in the beauty of both the text and the world it describes. The language is both powerful, with God speaking the universe as we know it into existence, and comforting, with its refrain of “and God saw that it was good.” This is without a doubt one of the most beautiful and evocative texts that has come down to us from the Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) world.

And yet my joy in the text is tempered a bit because I cannot read it without thinking of all the wrangling and rancour over this passage over the past two hundred years, especially in the Fundamentalist opposition to the findings of scientific investigations into the Earth and the history of life upon it.

Additionally, as someone whose anxieties surrounding the ‘truth’ of this story were largely resolved by gaining a better understanding of how it connects to other creation stories from the ANE, my experience of the text now also contains echoes of those stories, for good and for bad. (I think mostly for good!)

Encounter

This story has only one character, God. The God we meet here is all-powerful and infinitely creative. Unlike most of the creative types I’ve met, however, this God is able to delight in what God has made, declaring it all in the end to be “very good.” All this lends itself to an image of God that is powerful and creative, but also secure and loving. This is a God I want to worship and get to know!

Explore

A lot of questions come up for me when reading this passage. Most of these are better left for future posts, but there are two overarching ones that impact the whole story. The first is a doozy, the question of what we mean by ‘truth’ when it comes to the Bible and the stories therein. I think the best way to handle this question is to let it sit until we see what the story itself says, so we’ll put a pin in this for the time being. The second, which will take up most of this post, is the extent to which, and how, this story is related to other ANE creation myths. (Note: Some scholars, even ‘liberal’ ones, reject the term myth as being inappropriate for what Genesis 1-3 does. For some discussion on why I have no problem with that language, see my post on myth in my series on Biblical Genres.)

ANE Parallels

It has to be said right at the start that there is no question that the Genesis 1 creation story has a historical connection to ANE mythology, both generally, but also specifically, to the Babylonian text known as the Enuma Elish. So great are the parallels between the stories that even the most ardent Fundamentalist apologists accept the connection — they just insist that the biblical story came first. So what is this story and how does it connect to Genesis 1?

When we talk about ANE civilization, we’re talking about a vast period of time (roughly four thousand years), a large area of land (stretching from what is now parts of Turkey in the West through to parts of Iran in the East), and encompassing several distinct people groups, connected through trade, sequential imperial conquests, and cultural links. So the Enuma Elish is not the ANE creation story, but one of them, and one of the later of the bunch, likely dating to the late second millennium BCE (see Carr, Barton & Muddiman, and Sarna for good discussions of this).* To put this in terms of the Bible’s narrative, this means that this myth would have developed several hundred years after Abram’s departure from Ur (an important Sumerian city) for the land of Canaan. As the Bible and archaeological evidence both suggest, Canaan and its successor cultures were predominantly under Egyptian, rather than Mesopotamian, political influence from about 1500 BCE until the expansion of Assyria in the late 700s BCE. This geopolitical situation, along with the Enuma Elish’s own dependence on earlier ANE myths, strongly implies the Babylonian influence on the Genesis story, not the other way around. (I’ll return to this later.)

The story tells of a primordial water, associated with Apsu, the god of fresh water. Against this elemental being stood the monstrous Tiamat, the goddess of oceans. From their coupling came a succession of generations of gods. Annoyed by this loud gaggle of godlings, Apsu and Tiamat concoct a plot to destroy them, but are thwarted by an earth-water deity known as Ea (who was a later version of the Sumerian creation god Enki). A war between the gods ensues, with Tiamat and her allies facing off with the ambitious hero of the younger gods, Marduk, in a battle featuring raging winds and sea monsters. Marduk kills Tiamat and turns her dismembered body into the firmament (in ANE cosmology, this was a kind of ceiling that separated the heavens from the earth) and the foundation of the earth. Having emerged from the battle as the clear leader of the gods, Marduk takes on the trappings of Babylonian kingship and then goes about completing the creation, commanding the stars, sun, and moon into existence. But the gods complain that the new order involves too much labour, so, Marduk creates humanity to serve the gods, after which the gods throw a celebratory party that echoes Babylonian temple rituals. (This version of the story is largely drawn from Sarna (1966), 4-6).

There are a lot of clear similarities between the elements of this story and what we find in Genesis 1. Both stories feature:

- primordial waters

- the ocean / ‘the deep’ (the Hebrew word for ‘the deep’ in Genesis 1.2 is etymologically related to the Babylonian word used as Tiamat’s name)

- winds

- sea monsters

- the firmament

- the foundation of the earth

- speaking the heavens and earth into existence

- naming as a creative act

- creation of humanity

- divine leisure

And yet, as anyone familiar with Genesis 1 knows, despite these similarities the stories are remarkably different.

What seems to be happening here is something akin to an ancient, theological version of our contemporary trend of literary retellings of myths and legends. Today, these tend to come at existing stories in a way that highlights aspects or characters often sidelined in the versions that have come down to us (e.g., Madeline Miller’s Circe (2017) gives a character who plays a bit role in many important stories from Ancient Greece her own voice, perspective, and narrative). And I think that’s what’s happening in Genesis 1. Exposed to the Babylonian creation story during the Exile, faithful and educated Judahites retold it through the lens of their own monotheistic traditions. In their hands, this story of primordial violence becomes one of an intentional act from a loving God. The firmament and ground are no longer the dismembered body of a divine rival, but are spoken into existence with the same calm voice as the stars, the plants, and the animals. Even the frightening sea monsters are given attention here, not only created at God’s hand, but called “good.” Humanity is created not to be slaves for the gods, but to bear God’s “image and likeness” in the world. And instead of a divine celebration at having slaves to do their work for them, we have God simply resting after a “very good” week’s work.

All this to say, Genesis 1 is less the Bible’s explanation of the origins of the world (after all, it has at least three!) than it is an incredible, intelligent, and deliberate act of theological resistance. It reimagines the Babylonian story in such a way as to set the God of the Bible apart from and in contrast to the gods of their neighbours and captors. On this point, Walter Brueggemann writes:

Such a judgment means that this text is not an abstract statement about the origin of the universe. Rather, it is a theological and pastoral statement addressed to a real historical problem. … This [text] cuts underneath the Babylonian experience and grounds the rule of the God of Israel in a more fundamental claim, that of creation. (Brueggemann)

To return briefly again to the question of which story influenced the other, the narrative suggested here makes a lot of sense: Retelling the Babylonian story through a Hebrew theological lens would be a potentially powerful act of resistance for a people trying to retain their cultural heritage and withstand attempted assimilation by a dominant, imperialistic, culture. But if we flip it, it would make no sense at all. We’d have to argue that envoys from somewhere in the Mesopotamian cultural juggernaut towards the end of the first millennium BCE, visited the political and cultural backwater of the kingdom of Israel, heard the Genesis 1 creation story, and were so awed and challenged by it that they felt the need to rewrite their own myths to match its narrative beats, but without changing their myths’ polytheistic worldview, violence, or overall message. One would have to ask what would be in it for them. It strains credulity. This is why all but the most ardent Fundamentalist scholars accept the basic narrative of Genesis 1 being a theological reimagining of the Enuma Elish; the alternative simply has nothing to commend it, aside from upholding the reader’s own beliefs about the text which go far beyond any claim the Bible itself makes.

Genesis 1 in the Biblical Canon

Genesis 1 is not the only creation text in the Bible. Not only is there the subsequent story in Genesis 2-3, but there is also significant creation material in the Psalms (e.g., Psalms 8, 33, and especially 104) and in Job. (For Christians, we might also add the prologue to the Gospel of John here.) The thing that is often difficult for us to wrap our heads around is that of these Old Testament creation texts, there is good evidence that Genesis 1 is among the latest, likely emerging well after Genesis 2 and Psalm 104. The details of why are a bit out of scope for this post, but for now let’s just say that just as Genesis 1 shows a strong cultural influence from the 7th-6th C BCE Neo-Babylonian Empire, these other creation stories show familiarity with Canaanite and Egyptian stories that the Hebrews would have encountered far earlier. (As it happens, Genesis 1 is, for all intents and purposes, never referenced in the Hebrew Scriptures outside the Pentateuch (and even here, it’s very rare), which could also support a later date. It wasn’t until the Second Temple period that there seems to be much Jewish reflection on Genesis 1 at all, which stands in stark contrast to the Exodus, which echoes throughout the whole canon of Scripture.)

From a canonical perspective, then, the question becomes why the final editors of Genesis might have put this relative newcomer in this prime position at the start of the Scriptures. We of course have no way of truly answering this question, but it’s a fascinating one nonetheless. At the risk of getting ahead of ourselves, the Genesis 2-3 creation story is overall pretty ambivalent in its tone. It shows God as an anthropomorphic figure who doesn’t always get it right (e.g., at first thinking the animals could be an adequate companion for the human), and whose plans are almost immediately thwarted by the serpent and a gullible and irresponsible humanity. It’s a powerful story that shows some keen (if sad) insight into human nature, but it’s far from a rousing start, and it’s not really reflective of how God is presented in the rest of the Hebrew Bible. So, I think it would make sense that the editors of Genesis might want to start the book with a more majestic and optimistic passage, and one that is simultaneously more representative of the more mature monotheistic perspective we find in the Prophets and especially Wisdom literature (see Schorsch for more on this idea).

This last connection is interesting, as Genesis 1 has a lot of common themes with the Wisdom tradition, such as: the essential goodness of the world and possibility of shalom. And as the last of the major Old Testament intellectual traditions to emerge, there is evidence of a similar kind of Wisdom framing device elsewhere in the Scriptures, for example in the Psalter, in which the quintessential Wisdom Psalms 1 and 150 appear to be an intentional, largely after-the-fact framing of the whole collection. But is there any evidence in support of Genesis 1 being a later prologue added to an earlier version of the book? There may just be. The book of Genesis is organized in eleven sections, each introduced with the words “This is the account of …” But the first of these does not occur until 2.4, so the Genesis 1 narrative exists outside of the book’s internal structure, lending credence to the possibility of its later addition in order to frame the book within the more positive outlook of the Wisdom tradition (Walton 124).

Expand

I think it’s time to leave this introductory discussion about Genesis 1 aside and get into the specifics of the text. But before leaving this off, it’s important to ask ourselves what this story has contributed to our understanding. As I’ve mentioned before, coming to realize just how smart and creative Genesis 1’s reworking of the Babylonian myth was was a revolutionary, paradigm-shifting moment for me. Genesis 1 says so much about God, not just in its actual text, but also in how this text contrasts this God with the gods and goddesses of ANE mythology. Where ANE myths present creation as a violent, to some extent accidental act, with humanity created to be enslaved to the gods, our Bible starts with a story in which God lovingly and intentionally creates the world, ordering it specifically to suit the emergence of life, and human life in particular. And, rather than being created as slaves, humanity is instead created in God’s image and likeness, to be God’s official representatives within creation.

This is particularly beautiful considering much of the Old Testament paints a pretty ambivalent picture of the world and humanity, a story of human failure in a world that is full of temptations. That the editors of Genesis decided to put this story right at the start is a wonderful theological statement, a reminder of just how good both God and God’s creation (and us as part of it!) are.

This is a whole world of powerful meaning. And notice how questions of science versus religion, or biblical literalism didn’t come into play at all. I was originally going to put the scientific understanding of human origins as a ‘Challenge’ component to this post, but the more I thought about it, the more I came to see that these questions — as important as they may be theologically — are simply irrelevant to what Genesis 1 is trying to do. It wasn’t setting out to lay down a scientific, historical understanding of how the world was actually created; it was reimagining an existing story to make a theological point. And make it it did, and does. In this, I echo the great Walter Brueggemann, who similarly concludes:

At the outset, we must see that this text is not a scientific description but a theological affirmation. It makes a faith statement. As much as any part of the Bible, this text has been caught in the unfortunate battle of “modernism,” so that “literalists” and “rationalists” have acted like the two mothers of I Kings 3:16-28, nearly ready to have the text destroyed in order to control it. (Brueggemann)

In the next post, I’ll dig down deeper into the primordial state of affairs from Genesis 1.1-2.

* For full details on sources, see the series bibliography.

19 thoughts on “God among the Gods: Genesis 1.1-2.3”