As long-time readers of the blog will know, I’m a big reader. Literature is my main hobby and source of entertainment. Last year I started a bookish blog, which this Summer I transitioned almost entirely over to a dedicated Instagram account. In that capacity, I was recently given the opportunity to read an Advanced Review Copy of a forthcoming novelization of the life of Jesus, in which Jesus was assigned female gender at birth. While I won’t post a review until closer to its release date, I will say at this point that I found it incredibly disappointing — not because it played with Jesus’ gender, but because it did so little with that rich premise. This has got me thinking more about this subgenre of literature, literary Bible retellings — what makes them work, what makes them not work for me, as both a reader and as a Christian. And so I thought I’d write about this today in this space, during this ‘in between’ time on the blog.

These types of retellings are nothing new, but while they used to be predominantly aimed at evangelization, proselytization, or unofficial catechism, they are now mostly about exploring what’s missing from the Biblical record: the perspectives of women, for example, or the interior life of the characters, and so on. In this way, they’ve become a subset of the larger genre of myth / legend / fairy tale retellings, which has had a huge boom over the past decade. Like any genre, there are excellent examples of this larger ‘retellings’ genre, and a lot of mediocre ones. For me, for them to be successful, they generally do three things well (beyond the basics of being well-written and -plotted):

- First, they either foreground characters, incidents, or experiences our traditional sources for these stories keep in the background, or twist with the existing story just enough to allow it to speak in a different way. (This gender-bent Jesus book is an example of the second of these types. It didn’t work for me not because of the twist, but because it didn’t follow through with the promise of that premise.)

- Second, they bring the many elements of what are generally complex and muddled story cycles together in a coherent way.

- And third (and I’d say most importantly for this genre), they have a point of view. This is to say, they can’t just retell a story we already know; they have to be telling it for a reason and to say something new about it, about society, or about human nature.

Madeline Miller’s wonderful 2018 work Circe exemplifies all three of these characteristics: It tells the story of the sorceress Circe, who was a side character in many well-known Greek myths and legends; it brings these disparate elements from different stories together into a coherent narrative; and it does so in a way that shows Circe not as an evil witch, but as a woman repeatedly let down by those she loves (especially men). Another great example, which I just read last week, Herc by Poenicia Rogerson (2023), also does well by these three metrics: While it tells the story of Hercules — hardly a background character in Greek and Roman literature! — it does so from the perspectives of all the lesser-known characters who cross his path: his family, his wives, his companions and lovers, his enemies, and so on; in doing so, it brings together the complex and scattered Hercules story cycle into a single narrative; and, it has a specific point of view, portraying him as a tragic figure unable to keep himself from destroying what he loves.

I think these same criteria are a good place to start with judging biblical literary retellings. Foregrounding characters, incidents, or experiences that lie in the background of the biblical record is often a fruitful exercise, allowing us to see new things in the text. (This is true even in a non-fiction context, as Dr. Wilda Gafney’s masterful exploration of the Abraham story through the perspective of the enslaved woman Hagar demonstrates.) While the editors of the Bible have largely done the editing work of the second metric for us, good retellings can still fill in the gaps, adding depth and more coherence to what we have in the Scriptures. And, again most importantly, having a specific point of view about the events or characters is what really makes a biblical retelling worth undertaking: otherwise, we can just save ourselves the trouble read the Bible.

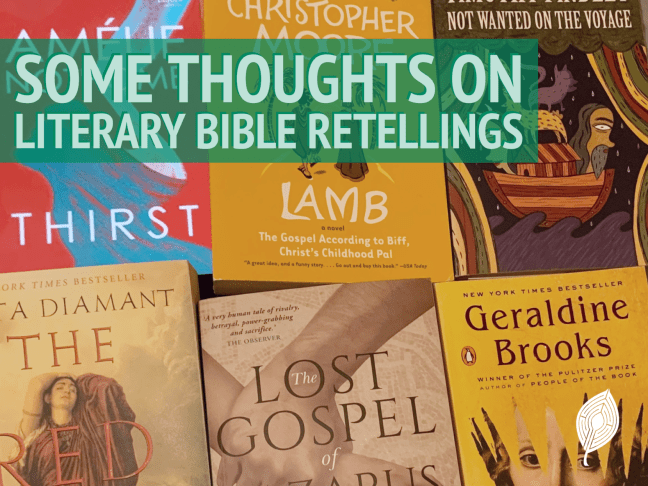

I’d like to spend the rest of this post talking about some of my favourites in this subgenre:

Old Testament Retellings:

- The Red Tent, by Anita Diamant (1997), which explores the dynamics among the women of Jacob’s household (roughly Genesis 29 and following), characters about which the Bible says very little but who are nonetheless critical to the story it’s telling. In so doing, it was able to bring forward elements present, but largely skipped over, in Genesis and bring new life to the stories, while also providing an interesting commentary on the lives of women in nomadic societies.

- The Secret Chord, by Geraldine Brooks (2015), which tells the story of David (roughly 1 Samuel 16 through 1 Kings 2) through the perspectives of those who loved and hated him (often at the same time); it may centre on David, but it’s really about the experiences of people like the prophet Nathan and David’s wives, such as Michal and Bathsheba.

- Not Wanted on the Voyage, by Timothy Findley (1984), which tells the story of the Flood (Genesis 6-9) from the perspective of Noah’s neglected, concerned, and terrified family. The only thing sympathetic about this Noah is that he was right about the coming disaster, but it’s a great exploration of the theme of obsession and the thin line between madness and genius.

New Testament Retellings:

- Lamb, by Christopher Moore (2002), a hilarious loose retelling of the story of Jesus from the perspective of his childhood best friend, who is resurrected in the late twentieth century to fill in the gaps of the Gospels. Some people don’t seem to have much sense of humour when it comes to their faith, but this is irreverent without being disrespectful, and even offers some wisdom of its own amidst the winking humour.

- Thirst, by Amélie Nothomb (2009), which explores Jesus’ psychology and internal experience in the last days of his earthly life. (This is probably my least favourite of the books I’m mentioning here, as I don’t think it did quite enough to make it great, but it still offers some interesting insights and lush writing.)

- The Lost Gospel of Lazarus, by Richard Zimler (2023, originally published in the UK as The Gospel according to Lazarus in 2019), which tells the story of Jesus’ last week (and life through flashbacks) through the lens of first- and second-century Jewish mysticism. This was one of my favourite reads of this year. I find a lot of books that try to situate Jesus within Judaism just use a lot of Hebrew or Aramaic vocabulary and expect that to do the work for them; this one is fully rendered and fits beautifully within what I known of late Second Temple Judaism and the mystical traditions that were around in and just after that time.