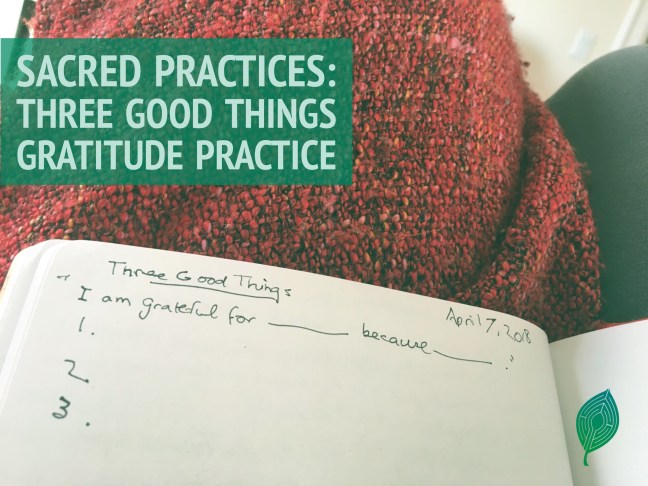

For this week’s sacred practice, I returned to an old favorite: the gratitude practice known as ‘Three Good Things.’ This is a practice I have been doing consistently for close to six years, and is the one practice I actively recommend to friends who are going through difficult seasons of life. Despite its simplicity — it is simply to write down three things for which you are grateful and why you are grateful for them, each day — I have found it to be transformative in my own life, and it’s one of the few practices with some form of scientific validation.

Background

Gratitude as a way of being in the world is at the heart of a religious or spiritual life. It is the core of the spirituality of the Psalms and remains one of the three elements of Jewish daily prayer. In Islam, the Qur’an associates gratitude with God’s ongoing generosity and gratitude is an important part of Muslim daily prayer. In Buddhism, gratitude is seen as a sign that one is seeing reality as it is, and it is further associated with freedom from impatience and greed. And, in Christianity, the Apostle Paul voiced the ideal of gratitude when he wrote “In everything give thanks; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you” (1 Thes. 5.18). Or, as Fr. Alexander Schmemann forcefully stated the matter in his final sermon: “Everyone capable of thanksgiving is capable of salvation and eternal joy.” So important is gratitude in the Christian imagination that the quintessential Christian worship practice is called the Eucharist, Greek for Thanksgiving.

Despite this venerable pedigree in the world’s wisdom traditions, it has only been in the past couple of decades that gratitude has begun to be studied in the Academy. But over the past two decades, researchers have linked gratitude to a multitude of benefits: general good health, higher levels of empathy and resilience, and reduced tendencies towards grudge-holding and revenge-seeking behaviours. Intentional gratitude practices, such as this week’s practice, have been found to reduce resentment, envy, regret, and anxious and depressive thoughts, and to improve mood and the length and quality of sleep.

The form of gratitude journaling known as Three Good Things has become the canonical exemplar of such practices, and with good reason. It’s simple, free, and takes only a few minutes a day to practice. In the words of Martin Seligman, one of the founders of positive psychology, “It works because it changes your focus from the things that go wrong in life to things that you might take for granted that go well and changing your focus to things that go well breaks up depression and increases happiness.” In an often cited study, participants were asked to keep a gratitude journal for just one week. After the week, their scores on tests measuring happiness improved by about 2%. However, follow-up tests showed that their scores kept on increasing long after the study was finished, increasing by 5% after one month and 9% after six months. Why? Because participants found the exercise so beneficial that they continued on with it after the week was over.

What is it?

Every day, write down three things for which you are grateful and why you are grateful for them. (For example, ‘Today I was grateful for my trips to the art gallery and museum because they made me feel connected to humanity and the ways genius and creativity have been expressed over thousands of years’, or, ‘Today I was grateful for the sunshine because its warmth reminded me that Summer is on its way.’)

My Week

Because this practice has been a habit for so long, this week was not particularly challenging. It was actually an easy week to do it too, as I was blessed by a visit from my mom and sister and enjoyed showing them around the city and playing tourist in my own town. But during difficult weeks, I find the practice a helpful reminder of what is good in life.

Reflection

I can honestly say that the ‘Three Good Things’ exercise has changed my life. As someone who has struggled with low moods since childhood, I can attest to the power — and staying power — of this practice for improving wellbeing. It’s a formalized way of ‘counting your blessings’, that age-old wisdom handed down by generations of mothers and grandmothers. The scientific rationale behind its effectiveness is that it combats “hedonic adaptation,” which is a fancy name for our universal tendency to get less joy from things over time. When something is new, we appreciate it and value what it adds to our life; but over time, it fades into what is ‘normal’ and so we come to take it for granted. The result is that the things that used to make us happy don’t anymore. The Three Good Things exercise is a formal way to fight back against this, to remind ourselves of what our relationships, possessions, abilities, and health add to our life. And, over the course of months and years, it can stop being simply a practice and seep into our bones and blood and become part of who and how we are in the world.

And really, it’s this movement that can allow us to “give thanks always for all things” (Eph. 5.20), which is one of the most challenging commandments in the whole Bible. As I’ve mentioned before, several years ago I underwent an intense spiritual trauma. While it was an experience I wouldn’t wish on anyone, I have come to a place where I am grateful for it, for what it taught me and for whom it made me. While it’s certainly possible that I would have come to this place without the ‘Three Good Things’ gratitude practice, I have no doubt that deliberately cultivating an attitude of gratitude has directly contributed to it and facilitated it.

I also can’t shake the Eucharistic overtones of this practice of gratitude. While I have already mentioned Fr. Schmemann’s famous last sermon, the theme of thanksgiving permeated his writings and formed the heart of his understanding of what it means to be human. In his masterful For the Life of the World, he wrote: “To bless God is not a ‘religious’ or a ‘cultic’ act, but the very way of life …. The only natural (and not ‘supernatural’) reaction of man, to whom God gave this blessed and sanctified world, is to bless God in return, to thank Him, to see the world as God sees it and — in this act of gratitude and adoration — to know, name and possess the world.” Our fundamental human nature, he says, is not to be homo sapiens, the human who thinks, but homo adorans, the human who worships: “The first, the basic definition of man is that he is the priest.” What he is saying is that the liturgical worship of the church is itself a kind of sacrament, pointing to and participating in the larger reality that God is “everywhere present and filling all things.” This is an idea that has tremendous consequences. For, if in thanksgiving the eucharistic bread and wine become vessels transformed into and transforming us through the Divine Life, and if this liturgical act is indeed a symbol of our whole life, then by extension any act of genuine thanksgiving can itself become the means through which we can experience God.

With such a view in mind, gratitude becomes not just a nice thing to keep in mind at the end of the day, and not just a tool to improve our mood or to help us sleep, but one of the most powerful spiritual tools at our disposal. Reminding ourselves of what we have to be thankful for, offering our prayers to God with grateful hearts for the blessings we have, or have had, has the power to revolutionize our experience of life for the better and to help us through the difficult times we all go through. And while, the Three Good Things exercise may not in itself be able to accomplish all this, it is certainly a good beginning.

8 thoughts on “Three Good Things”