We spent the couple few weeks looking through the creation story in Genesis 1.1-2.3. We saw that that text, likely dating to the seventh century BCE, took the common Babylonian creation myth and twisted it, retelling it for its own monotheistic purposes. It’s a beautiful, optimistic story, but while it absolutely captures the majesty and wonder of creation, it doesn’t much resemble the difficult world we’re used to living in. Well, if a depressing, brutally honest story about human nature and how we mess everything up is what you’re looking for, look no further than the next story in the Bible, the second creation story found in Genesis 2.4-3.24.

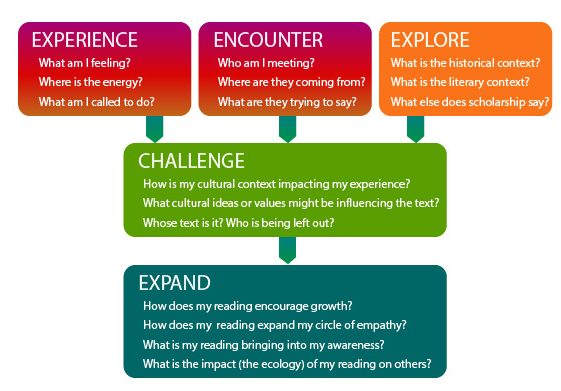

Today I’ll be looking at this story in the big picture, before zooming in to its many interesting details in upcoming posts. As a reminder, these studies will be guided by my Integral Hermeneutic Method, with its five steps of Experience, Encounter, Explore, Challenge, and Expand:

Text

The full text of this story is too long to include here. Have a look in your Bibles, or check out the text here: Genesis 2.4-3.24.

Experience

I’d describe my experience reading over this text as ‘muddled’. On the one hand, it seems to be a perceptive, if depressing, critique of human nature. On the other hand, it’s hard not to notice some big differences between this story and the one preceding it. It also seems significantly more mythological than Genesis 1, portraying God in very human terms, not just ‘speaking’ and ‘making’, but performing surgery and walking in the Garden. God also comes across as rather fallible here, not understanding Adam’s needs and then having his plans almost instantly thwarted by the serpent’s manipulation. In other words, it’s a story that rings true psychologically and spiritually, but it feels like it comes from a different universe from the Genesis 1 story, and doesn’t put anyone — including God — in the best light.

Encounter

From God being the only character in the Genesis 1 story, suddenly we meet a number of characters here. We still have God, though here specifically identified with the divine name associated with the covenants with Abraham and Moses, YHWH. But again, this God comes across very differently from the unopposed, omnipotent sovereign of Genesis 1. We also meet Adam, the first human, formed from the mud of the clay. We know little about Adam, except for the fact that they are to tend the garden, and that they are lonely. Adam rejoices when a suitable partner is found, one just like him. Then we meet the woman, created as a companion for Adam. She is shown to be open and curious, but also gullible. When misled by the serpent, both Adam and the woman (later named Eve) refuse to take responsibility for their mistake, instead casting blame on others. And finally, we encounter the serpent, a mysterious figure about whom is said very little, but who introduces conflict into the biblical story for the first time, misleading the humans.

Explore

The first two steps brought up a lot of questions for me. Most of these will have to wait until the more focused posts, but for today, the big questions I’d like to explore are:

- How does this story compare to the other creation text(s) in the Bible?

- Are there any parallels to Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) mythology, as we saw for Genesis 1?

- What is the overall message of this story?

Genesis 2-3 and Creation in the Bible

Genesis 2 stands apart among the creation stories in the Bible. As you can see in the Comparison of Creation Texts, it pays no attention to the creation of the basic structure of the world, but only to the things that fill it. The conflict and divine speech motifs are both missing in this story, which pictures God instead as a craftsman or artist. The story also contains many elements not found in the other creation stories: the Garden (though, this is referenced briefly in Ezekiel), the two trees, specific references to agriculture, the creation of biological sex, and the Fall narrative are unique to Genesis 2-3. So, we can rightly call it an outlier among the biblical creation texts, which makes it all the more interesting to study.

That Genesis 1 and 2 were written by different authors, with different theological emphases and aims, is one of “the oldest and most secure conclusions of historical-critical analysis of the Bible” (Carr). In addition to its consistent use of the divine name YHWH instead of the general term ‘God’, the two stories are exceedingly difficult to reconcile, since the order of creation of plants and animals is completely different:

| Genesis 1 | Genesis 2 |

|---|---|

| Heavens and Earth | Earth and Heavens |

| Waters | Waters |

| Vegetation | The Human |

| Sea & Sky Animals | Vegetation |

| Land Animals | Birds & Land Animals |

| The Human | The Woman |

Here, the human is among the first things made, rather than the last, as Adam pre-dates plant and animal life. (It’s interesting how in their insistence on harmonizing the two creation narratives, literalists have to ditch a literal reading of the chronology of Genesis 2 entirely!) In a sense, Genesis 1 builds up a world for humanity to inhabit, while Genesis 2 builds a human, then gradually figures out how to meet the human’s needs.

While there is no consensus, most of the resources I consulted think that the Genesis 2-3 story is the earlier of the two stories. Its theme of the dangers of prideful self-assertion fits with the late monarchy’s concerns of law and order, focus on the divine name, and rather realistic and ambivalent perspective on human life (Carr, Brueggemann). *This is in contrast to the high-brow, universal, Wisdom themes of Genesis 1, which could be said to was written as an antidote to despair (Brueggemann). They also note that this story begins with the formula “These are the generations,” which is a consistent pattern in Genesis that marks what we could think of as something like chapter titles in the book, a feature missing from Genesis 1, and therefore a possible indication that Genesis 1 was appended to the start of the book during the editing process (Smit 26).

One thing that may be surprising to Christian readers, used to thinking of Genesis 2-3 as “the premise for all that follows” in the Scriptures, is that, in the Old Testament, and for much of Jewish history, this is actually “an exceedingly marginal text” (Brueggemann). Aside from references to Adam in genealogies and a mention of the Garden of Eden in Ezekiel 28.10 (which doesn’t sound all that much like the version of the Garden here!), it is not referenced again in the entirely of the Old Testament canon.

So, whatever this story may say to us, it stands alone in a lot of ways in the Bible.

Genesis 2-3 and ANE Cultures

While Genesis 2-3 may stand alone in the Bible, that does not mean it has no corollaries at all. Just that we have to go further afield to find them. There is no ‘smoking gun’ linking Genesis 2-3 to any particular story, as there was for Genesis 1, which seems to be theological reimagining of the Babylonian Enuma Elish. Rather, it employs common motifs or ideas that place it soundly within the mythological and literary traditions of the ANE (Carr, Brueggemann, Walton). Some of these elements include: The opening description of the pre-creation state, the Garden, creation of humanity from clay, creation of humanity for the purpose of agriculture, the tree of life and theme of mortality, and the gradual illumination of the human intellect. We’ll look at these more in future posts, but suffice it to say, Genesis 2-3 is a product of an ANE culture, and made use of existing images and motifs to make its often unique theological (and anthropological) points.

Meaning

But what exactly are those theological and anthropological (we might also add spiritual and psychological) points? This will, of course, emerge more as we dig into the details of the story. But it’s clear from the outset that Genesis 2-3 shifts the focus away from God and onto humanity (Brueggemann). And so we have a resulting shift away from the majestic and optimistic, Wisdom imagery of Genesis 1 to something far more pessimistic, realistic, and gritty. Genesis 1 exults in a world full of meaning, potential, and order. Genesis 2 brings us back to reality — a recognizable, human reality where nothing is ever as it ‘should’ be, our loved ones let us down, and we are quick to lose nerve and point fingers.

The story offers no answer to the origin of evil or sin, but simply assumes it as a given of the world. It doesn’t even give evil the respect of being the primordial chaos that existed before creation, as most ANE creation myths did (Sarna (1989) 16). Rather, the source of the harsh realities of human existence is shown to be disobedience to God, yes, but also sowing seeds of doubt or confusion in others, allowing oneself to become drawn in by such pot-stirring, and refusing to take responsibility for our actions. In other words, it’s about the break-down of mutually respectful relationships: The serpent breaks faith with God and the woman, the man and woman break faith with God, then break faith with each other, leading to long-lasting consequences for the whole created world. In other words, the story starts from a place of connection, and ends in alienation (Brueggemann). Except for God, who remains in faithful relationship — giving them clothes to better protect them in the harsh lives that await them outside the Garden.

It’s interesting that the particular focus of the disobedience here is about the acquisition of knowledge. We’ll have to explore this idea further down the line, but it’s good to put it in our minds here at the outset. The Bible as a whole seems to have an ambivalent attitude towards knowledge. On the one hand it encourages us to glean what we can about God through studying the world around us; on the other hand, it questions the importance and benefit of such knowledge. Even as someone who’s dedicated my life to knowledge, I think this ambivalence is warranted. Certainly knowledge about the world often comes with warnings about the many ways it can go — and is going — wrong, which leads to increased anxiety. And there’s the old science problem of ‘Can we do this?’ (split the atom, dam this river, create a microscopic singularity in a lab, clone a dinosaur) versus ‘Should we do this?’ Knowledge is power and helps us to better understand and shape the world around us, and yet knowledge is always partial and we’ve gotten ourselves into deep trouble by acting without truly understand what we’re dealing with. It’s a catch-22, and so I’m not at all surprised by the ambivalence we see in the Bible. We cannot be grown ups without shattering the innocent illusions that come from ignorance; yet that disillusionment always feels like a very big loss.

I mentioned earlier that, over and against the central importance this story has taken on in Christianity, this is a marginal story in the Old Testament. But I do think we can still say the rest of the Old Testament picks up the story from where it left off. But instead of being a cataclysmic event that changed human nature on an essential level, the Old Testament treats it as a representative event that revealed human nature — just the first of many falls from grace that God acts to mitigate (Bruegemann).

Expand

So, how does this cursory look at Genesis 2-3 contribute to our understanding of the book as a whole? Where Genesis 1 painted a majestic picture of the creation of the world and humanity’s vocation within it, Genesis 2-3 brings us down to earth and the disappointing realities of life we know so well. If we see our world and selves in Genesis 1, it’s when we’re at our best. But, most of the time, we’re squarely in a Genesis 3 reality. Irrespective of which story came first, it’s instructive that the Bible offers us both: one optimistic and aspirational, one pessimistic and realistic. Both reveal their own respective truths about the world around us, and we’d lose something important without either one of them.

* Please see the series bibliography for full information.

9 thoughts on “Creation, Take 2: Genesis 2.4-3.24”