Over the millennia, scholars and devotional readers alike have come away from Genesis 1 awed by the grandeur of God’s vision and plan. It’s a story in which everything has its place and God systematically sorts the primordial undifferentiated mess into things that have form and purpose. This sense of orderliness is heightened by the regularity and repetition of the text itself. These are the two themes I’ll be focusing on today:

- What should I know about the cosmology of Genesis 1?

- How does the conventional pattern of activity in the story contribute to how we understand it?

(As a reminder Part I included the text in question, the Experience & Encounter steps of the Integral Hermeneutic method for this passage, and the Explore, Challenge, and Expand steps for the first two questions that emerged, about the role of divine speech, and creation by separation.)

Explore

The Cosmology of Genesis 1

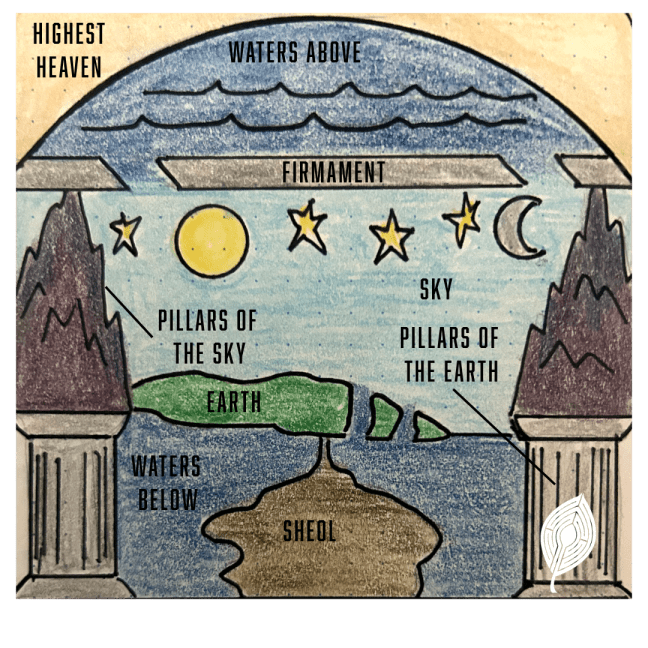

It’s clear from a cursory reading of Genesis 1 that this text is working from a very different understanding of the universe from what we’re used to. There’s a primordial ocean, a vault (’the firmament’) that holds up the waters that periodically descend in the form of rain or snow (see Genesis 7.11 for this detail). The ‘waters below’ are collected together to reveal the land, and the sun, moon, and stars are placed to move across the vault according to a regular pattern. Nothing about this is unique to Genesis 1 or to the Bible as a whole; rather it conforms to the generally accepted cosmology of the Ancient Near East (ANE) (Barton & Muddiman 42, Walton & Keener, Barker, etc.).* To put this general ANE cosmology into a picture, it looks something like this (pardon my hand-drawn and coloured diagram!; see also Sarna (1966) 5):

In ANE mythology the different parts of the divine ‘built environment’ are either repurposed from the dismembered bodies of the creator god’s vanquished enemies, or are considered divinities in their own right. But of course, in the thoroughly demythologized version we get in Genesis 1, they are just receptive elements shaped and given function by God. As we saw last time, when God speaks, they listen and so cease to be ‘formless and functionless.’

Narrative Structure

Now that we’ve looked at how Genesis envisions the structure of creation, let’s turn to how this sense of orderliness is mirrored and heightened by the structure of the story itself (Barton & Muddiman 42, Tuling, Carr, Sarna (1989) 4). The whole story is organized to reinforce the belief that God’s sovereignty and authority are unquestioned and the world is an orderly, purposeful, and predictable place.

This is probably best seen in a table that shows the regular patterns in the story:

| CREATION ACT | SPEECH | ACTION | RESPONSE | ASSESSMENT | BLESSING | SEPARATION | NAMING | DAY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | And God said | and there was… | …the light was good | And God separated | God called… | One day | ||

| Sky | And God said | God made.. | and it was so | Let it separate | God called… | The second day | ||

| Land and Sea | And God said | and it was so | … it was good | …be gathered together | God called… | |||

| Vegetation | And God said | and it was so | … it was good | (of every kind) | The third day | |||

| Luminaries | And God said | God made … | and it was so | … it was good | … to separate | The fourth day | ||

| Sea & Sky Animals | And God said | God created… | …it was good | God blessed them | (of every kind) | The fifth day | ||

| Land Animals | And God said | God made… | and it was so | (of every kind) | ||||

| Humans | And God said | So God created… | and it was so | (it was very good) | God blessed them | (to rule…) | The sixth day |

As we can see from the table, the eight elements of the pattern aren’t seen for every creation act, but each creation act has between four (the land animals) and seven (humanity) of them. The only part of the pattern to show up without fail is divine speech, which we talked about at length the other day. I’d also argue that separation, the other theme we’ve already explored, could be said to appear in all eight creation acts. It’s mentioned explicitly only four times, but three times there is division within what is created (“of every kind,” or “each according to its kind”), and the eighth act ascribes a role to humanity that separates it from the rest of creation. If, as we saw, differentiation is really about assigning purpose and destiny, then we can say that this happens in every creation act.

Helping Actions

Another part of the pattern is what we might call a helping action following the act of divine speech. There doesn’t seem to be much rhyme or reason to when this is included; it could just be switching it up for the sake of narrative interest. What is noteworthy is that two of these supporting acts are described using bara’, that strange word for creation that is used in the Bible for God alone. The scholarly consensus about this is that it marks these two acts as being of particular importance. It first appears (after 1.1 of course) when describing the creation of the animals of the sea and sky. At first glance, there doesn’t seem to be much reason to set this act apart from the others, but a close read finds that the sea monsters are the primary direct object, with all the other sea and sky creatures added on at the end (Sarna (1989) 10). As we’ve seen throughout this series, sea monsters were common antagonists in ANE creation myths, including the Enuma Elish. Even in the most heavily mythological biblical creation text, it speaks of God “break[ing] the heads of water-dragons and crush[ing] the head of Leviathan,” a sea monster in service to the sea god Yam in Canaanite mythology (Psalm 74.14). But here the text goes out of its way to say that the sea monsters are not in opposition to God, but are intentionally created by God as part of creation (cf. Psalm 104.26, which humorously says that God made Leviathan to “play” in the oceans). Humanity also gets this special treatment, which is fitting for a text which, as we’ll see more in the next post, sets up humanity as the pinnacle of creation. (As Carr points out, the whole story can be read as “a highly orderly description of God’s development of a human-inhabited biome,” in other words, not just God creating the world, but creating a world for us (Carr, cf. Brueggemann).

Response

The next part of the pattern is an acknowledgement or response. On the first day this is marked by “and there was light;” the rest of the time the text simply says “and it was so.” The only creation act for which this does not appear is the creation of the sea and sky animals, and it’s so unusual in the progression of the story that the Septuagint recension of the text added back in. (It could also be that the Hebrew recensions took it out, but it is more common for texts to increase regularity than to introduce irregularity.) The point of the acknowledgement seems to be to once again show God’s authority: When God speaks, God’s word is done.

Assessment

One of the most beautiful parts of the Genesis 1 story is the regular assertion that God assesses creation as good. This appears in five of the eight creation acts, and reappears in emphatic form at the end of the sixth day when God calls the whole creation “very good.” The specific construction begins with “And God saw….” Sight is often used as a metaphor in the Bible for understanding, recognition, and even provision. An example that comes to mind is the story of Hagar, who gives God the name “El-Roi,” “The God who sees me” (Genesis 16.13). So, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that this isn’t just God ‘looking at’ things, but truly seeing them as they are. And in doing so, God sees them as good: Everything has its own value and role to play (Bauckham 178). This is a remarkable aspect of Genesis 1, utterly unique and revolutionary in the ANE world (Sarna (1966) 18, Barton & Muddiman 42). Its optimism is all the more remarkable if the story dates to the Exile, when it would have been a radical act of faith to call a world in which the people had been dispossessed and exiled “good.”

Naming and Blessing

The first three creation acts are unique in that God names what is created. It’s an interesting detail as these are the acts describing the structure of creation. Naming comes up again in the Genesis 2 story, where Adam is tasked with naming the animals. I think this is an intentional division of responsibility. As we’ll see in the next post, part of God’s blessing of humanity is to exercise a kind of sovereignty over the animals. So it could be that God names the essential structures of the world (light, sky, sea, land) to demonstrate direct rule over them, while leaving humanity to name and have authority over what fills them (Carr). (Left out of this schema is vegetation, which does not get named at all in Genesis. But the vegetation is in a strange position in the narrative anyway, being seen as part of the built environment rather than part of the “living creatures” that fill it up, yet also set apart from the structural elements by being given as food for the animals (1.29-30) (Barton & Muddiman 43).)

In addition to the three creation acts whose results are named, two — the sea and sky animals and the humans — are also blessed. The basic blessing given to both is the same, to “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the waters/sky/earth (1.22 & 28). To the human is given the additional blessing to “have dominion over” the animals of sea, sky, and air. There is also a third blessing in the Genesis 1 story, as God will later also bless the seventh day in 2.3. Blessing puts us in the realm of the priestly; it is a liturgical or ritual act. Ending as it does with a kind of crescendo towards blessing, we might go so far as to consider the point of the whole story to be about God’s priestly blessing of creation.

Days

The final piece of the organizational pattern of Genesis 1 is its famous six-day structure. This structure is simultaneously essential in the story and kind of shoe-horned into it. There are after all eight creation acts that are made to fit rather artificially into a six-day schema. This structure is designed to set the seventh day apart as a day of rest. This structure is both strongly linked to and distinct from surrounding ANE cultures: Seven was certainly understood to be a sacred number in ANE societies, representing perfection or culmination (Sarna (1989) 4, Bauckham 177). But Genesis 1 is unique in building a creation myth around the number seven and in associating it with rest.

So then, together, these regular patterns within Genesis 1 heighten to story’s message of God’s authority and the goodness and trustworthiness of creation.

Challenge

If it were up to me, it would be fine to leave it at that. There are good cultural reasons why the story reads as it does, but also good cultural reasons for it standing out against the background of other ANE (and biblical!) creation stories: The Genesis 1 story is crafted to highlight the number seven because seven was a sacred number in ANE cultures and it was sacralized in a particularly important way in Hebrew culture through the Sabbath. In the same way, it uses the basic cosmology of the ANE because that’s just what was around; it’s a perfectly reasonable pre-scientific cosmology.

However, at this point, we finally have to address the issue of biblical literalism and the challenge of science. Biblical literalists would argue against the way I’ve talked about these issues, asking why ANE cultures couldn’t share this cosmology and value the number seven because of some distant remnant memory of the one, true creation story. For me this argument is countered by a few things. The most obvious is the unimpeachable weight of the sciences — not just the theory of evolution, but fields of geology, physics, astronomy, palaeontology, archaeology, genetics, and molecular biology — which are unanimous in support of a very, very old earth with a very long history of life upon it. In order to reject all of this, we’d be left having to believe that the whole of creation was intentionally built by God as a conspiracy to test our faith. And to me that’s just completely inconsistent with both the character of God and a ‘good’ creation (which we’re told will reveal to us truth) revealed in the Scriptures. And all that just to uphold a belief in a certain kind of authority for the Bible that it does not even claim for itself.

But, science aside, there is good reason to assume the Hebrews adopted these shared aspects of ANE culture rather than receiving them as divine revelation. The arguments here are closely connected. First, the seven-day week and basic cosmology were very common from the beginning of ANE civilizations, and are attested long before the Hebrews were on the map, let alone before Genesis 1 was circulating (Sarna (1989) 14 and (1966) 20, Barton & Muddiman 43). Second, asserting that Genesis 1 must take priority anyway doesn’t explain the data, since the seven-day week is never brought into any other ANE creation story. One would have to insist that the ancient Sumerians retained a strong cultural memory of the number seven as an organizing principle, but not its associations with creation — despite the fact that all ANE creation stories explain important aspects of how their civilizations work. Connected to this, third, the association of creation with the number seven is not even a consistent feature of how the Bible talks about creation. As we’ve seen, there are a number of creation passages in the Old Testament and Genesis 1 is the only one in which the number seven features. In fact, biblical scholars have pondered since at least the 1700s whether the six-day organizational scheme was a later addition to the story crafted to give the Sabbath tradition additional grounding (Carr). They noted significant differences in tone in Genesis 2.1-3, which talks about God’s resting on the seventh day, from the rest of the story, and the fact that the eight creation acts are awkwardly fit into six days of creation. (Remember also that the Sabbath is given two different justifications in the Pentateuch, only one of which grounds it in creation (Exodus 20.8-11; Deuteronomy 5.12-15 grounds Sabbath-keeping in Israel’s freedom from slavery.)) All this to say, it’s far simpler, cleaner, and sensible to assume these elements Genesis 1 shares with ANE civilizations are taken from the existing cultural milieu, rather than the other way around.

I’ll also add that interpreting Genesis 1 in a literary, rather than literal, way is far from a recent development caused by the rise of modern science. While the Church Fathers did not have to contend with science, they did have different approaches to how the six days of creation should be interpreted and how they fit in with the dominant cosmologies of their own time. Many of the fathers insisted on interpreting the six days “literally.” However, before reading too much into this, we have to note that for them, ‘literal’ readings were not in opposition to literary readings, like they often are today, but rather to spiritualized or allegorical readings. Often a Church Father will talk about the importance of a literal reading, but their actual discussion is literary, talking about the six days as an organizational or paedagogical (i.e., ‘for teaching’) structure (see, for example St Gregory of Nazianzus, Homily on Genesis 44 and St. John Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis 3.12). For his part, Origen said outright that much of the language of Genesis 1 was intended to be figurative: “I do not think anyone will doubt that these are figurative expressions which indicate certain mysteries through a semblance of history and not through actual events” (De Principiis 4.3.1). And St Irenaus of Lyons, the earliest of the Church Fathers to provide extensive comment on Genesis 1, was open to different ways the days of creation could be interpreted, to the point of suggesting that all 930 years of Adam’s life took place on the sixth day of creation (Against Heresies 5.23).

All this to say, we’re in very good company to insist that the six days of creation in Genesis 1 are intended as a literary feature justifying the Hebrew week and sabbath traditions rather than as history or science.

Expand

So then, how does all of this contribute to our understanding of Genesis 1? If 1.1-2 show the un-created state of things to be formless and purposeless, Genesis 1.3-25 demonstrates through a highly stylized narrative that God has brought form and function to creation. Everything has its place and purpose, and runs according to God’s plan. And all this is declared to be “very good.” This literary approach to the text allows its meaning to shine through without getting bogged down in unhelpful questions about science and ‘how’ the Bible is true, questions which are foreign to the text itself anyway.

In the next post we’ll turn to what, according to traditional readings of the story, is the pinnacle of God’s creative act, us.

* For full information, see the series bibliography

14 thoughts on “According to Plan and Purpose: Genesis 1.3-25, Part II”